Expedition Journal

Powerful Explosions in California

Shortly after midnight, on August 11, 2007, a large fireball was witnessed throughout northern and central California by thousands of people.

The fireball began to break up over the Sierra Nevada range, moving in a south easterly direction. Residents in the Pinecrest area described a terrifying noise, and several people indicated they were nearly knocked off their feet, while inside their homes, from the energy released during the break up.

Tracking the flight path

After several days of gathering information and preparing equipment, I drove to central California and began interviewing eyewitnesses in the Bishop area. I continued driving through Yosemite Park, and then in the Big Oak and Groveland areas, I found many eyewitnesses in a short period of time. Over the next week, I interviewed hundreds of eyewitnesses, from Chinese Camp up to Sutter Creek.

Larry Stange had captured the event on his Yuba City all sky camera, and the event had registered on several seismometers on Mammoth Mountain. Using these two invaluable pieces of data, along with dozens of good eyewitness accounts from the hundreds of witnesses I had interviewed, I was able to calculate a flight path – and a dark flight model with reasonable accuracy. The termination point was in one of the most remote regions of California, high in the Sierra Nevada.

After more than three weeks of gathering data, I was convinced that the meteorite had fallen in an area only accessible by hiking or horseback. As it was nearly 13 miles as the crow flies from the nearest road, formidable mountain trails and inhospitable terrain lay between the location and my nearest point of entry.

Packing into the Sierras

I met up with Matt Bloom, owner of Kennedy Meadows pack station. He set me up with a horse and mule team loaded with equipment and provisions. He had clients camped at Huckleberry Lake, very near the flight path, and I set up my camp with them. After instructing everyone in camp on what to look for during their daily routines of fishing and hiking, I set out the following morning for my proposed fall area.

The first morning, sitting on a ridge line due east of Gillette Mountain, I surveyed the search area. The terrain was much worse than I had imagined. Magnificent valleys separated the fall area in at least three different places, and huge granite mountains with sheer cliff faces jetted up on several sides of where I needed to be.

The first day almost ended in disaster. I descended down into a valley crisscrossing different layers of rock and sometimes moving hundreds of yards in one direction just to find a way to drop straight down 40 or 50 feet. When I finally arrived at the bottom, I realized how much time and energy had been expended. The other side was no less formidable, and as the light changed became apparent that the valley I was targeting had been split in half by a glacier. The route that I had chosen to navigate was impossible.

Realizing that, if I didn’t move quickly, I would be spending the night in a bear-infested region just across the Yosemite Park border, I took a chance and climbed a very large crevice connecting to a tributary into the small valley above me. At about four hours after dark, the valley finally dead-ended at a cliff’s edge – over a vast valley cut far deeper into the ancient granite rock.

I carefully worked my way out onto the edge of the cliff face where I could have a clear view of this canyon that separates Yosemite from the Stanislaus forest. After several minutes of adjusting my eyes to the light, I finally saw what I was looking for. Dimly visible through the trees, I spotted several campfires far below me. My gamble had paid off, and I would be sleeping in my tent that night after all.

The following day I headed towards Olive Lake, which was my new primary search area. Within an hour or so, clouds begin to build up, and I knew that a large storm was coming. Rain and lightning were on me before long, and I took refuge in a crevice and waited it out. Lightning struck within 100 yards of my location, and after the rain ceased, I attempted to get my bearings with my GPS. But it was fried.

After transferring camp coordinates to my backup GPS, I spent the rest of the evening crisscrossing my way back towards camp. It was clear to me that this environment was certainly not a safe place in which to work alone. But because of gun laws in California, I was unarmed in one of the most densely populated bear regions in North America, working far off the beaten trail in areas almost never inhabited by humans. I made the decision that night to return at a later time with a team of meteorite hunters, and the next day it took me eight hours to ride out horseback.

A Single Stone is Found!

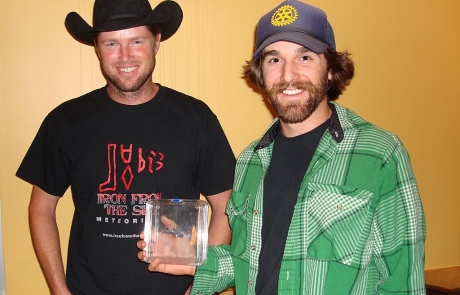

Several weeks later, while hunting the Puerto Lapice strewnfield in Spain with Robert Haag and Mike Farmer, I received an email from a man named Ben Deutsch. He was a member of a local Sierra Nevada hiking club that I had instructed on what to look for and where, and while hiking in the Stanislaus Forest he had come across an 18.35-gram, fresh chondrite between Five Acre Lake and Cow Meadow Lake – just below the runoff from Red Canyon Lake.

Upon returning from Spain, I met up with Ben in Sonora, California, purchased the stone, and mounted another expedition into the area – this time backpacking with Shauna Russell. We spent two days backpacking into the area, and if I had it to do over again, I would have certainly enlisted the help of Matt Bloom again. But we did it the hard way.

We camped just below Red Canyon Lake and hunted for several days. Just before leaving the area, we were met by Ben and a friend of his, and they showed us the find location. We exchanged information regarding which areas had been searched, then Shauna I began the long journey back. Having a better understanding of the lay of the land – and with gravity now at our favor – we descended out of the High Sierra and arrived back at our vehicle with several hours of daylight to spare.

In Closing

It was very fortunate that Ben was keeping his eyes open and recovered this small, single stone – only California’s second witnessed fall. Red Canyon Lake is just across the canyon from Olive Lake, my second search area. While we were not able to make it to Olive Lake because of the canyon separating the two areas, I still feel that the Olive Lake area was the best bet for finding more stones. But the severity of flooding in searchable areas makes further recovery extremely unlikely, if at all possible.

IT WAS CLASSIFIED AS AN H5 ORDINARY CHONDRITE.

Meteorite Details

| Name: | Red Canyon Lake |

| Location: | Tuolumne Co., California, USA |

| Classification: | H5 |

| Witnessed: | Yes |

| Fell: | August 11, 2007 |

| TKW: | 18.35 grams |