Expedition Journal

Brilliant Fireball Witnessed in California

The morning of April 22, 2012 began as just another day for the residents of the Coloma Valley resort communities, nestled beside the South fork of the American River. As usual, it was nothing but clear skies and perfect weather for this tourist destination, which was made famous by James Marshall’s discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in 1848.

At 7:51 am, a brilliant fireball appeared in the skies above the valley, descending from the east and fragmenting nearly overhead, releasing 3.8 kilotons of energy. A blast of wind descended down the valley, followed by thunderous sonic booms.

I was notified of the event within a few hours and began readying my gear and collecting information as it became available. The following day Marc Fries and Rob Matson found radar signatures associated with the event. I left Bullhead City that evening and arrived in the Coloma area at 4:00 am the following day.

The Search Begins… With a Flashlight

I began to search in an area with multiple altitude radar returns centered along the axis, starting with parking lots and roads with the aid of a flashlight until daylight. I then began talking with locals and driving the roads, hoping to come upon meteorites while familiarizing myself with the area.

After several hours I returned to the Lotus Park area and began to search clearings and trails. Shortly after 10:00 am, I was walking along a stretch of bare ground between the highway and parking lot of Lotus Park when I noticed a small charcoal gray object several feet to my left. I bent down and picked up the stone, and as I rolled it over I was astonished to see a typical frothy fusion crust with a bluish silver hue!

I stood there in shock for more than a minute, my hands trembling. I felt lightheaded as I realized that I had just found the first meteorite from this event. It was clearly an extraordinary class of meteorite, a carbonaceous chondrite, and appeared to be of the CM group.

I made several calls to colleagues and discussed my situation, knowing that this type of meteorite is very friable and would not last long in such a wet environment. I made the decision to go public with my find and begin what would surely become a massive search effort for such a scientifically extraordinary type of meteorite.

In order to document my find with the scientific community, I contacted Dolores Hill with The University of Arizona and informed her of my discovery. Within hours I was joined by Peter Jenniskens, of The SETI Institute, along with several other scientists.

Just meters from where my truck was parked, Peter found a second stone that had been run over and crushed in the middle of the parking lot. We excitedly weighed both of our discoveries. My piece weighed 5.5 grams, and Peter’s find totaled 4 grams.

We were soon joined by reporters from every national news network. Within hours the story went worldwide, and soon mobs of people showed up looking to strike it rich by finding a piece of this cosmic treasure. I soon realized the irony of my find: just as James Marshall’s discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill launched the California gold rush, my discovery had started a scientific gold rush. The Sutter’s Mill fall was soon to become the largest meteorite hunt in history.

The following day I was joined by fellow meteorite collector and close friend Dave Gheesling. He soon recovered two crusted fragments from the stone that had been shattered in the parking lot.

The next morning, Tanya McAllister and I were walking a small, paved road east of the river. She bent down, picked up a stone, and took several steps towards me asking, “Is this one?” She then brushed off her suspicion with a “Naw” and stretched out her arm to throw the stone into the grass. I noticed a frothy black crust as she drew back and yelled “Oh my god. That’s a piece!” Right at that moment, Robert Woolard and Mike Farmer pulled up. Tanya handed me the stone, and I ran up to their car yelling, “She found one!”

Gold Fever Returns to Sutter’s Mill

The Sierra Nevada House became Meteorite HQ. Nestled beside the American River, this former brothel of the late 1800s now offers fine dining, a bar, and rustic rooms for rent.

As locals learned what to look for, pieces started to be found in yards and around businesses. Meteorites were soon being brought in for confirmation and often offered for sale on the spot to scientists and dealers. Many of the locals had taken a serious interest in the meteorite rush, and restaurants and coffee shops began to rename dishes to “cash in.” One local restaurant offered the “Meteorite Burrito,” and a local coffee shop specialized in “Meteor Mocha.” Just as in the times of James Marshall’s gold rush, people were cashing in on the “gold fever.”

Dave and I spent the next few days securing permission to hunt private properties. It was evident by this point that finds would be few and far between. Shortly after Dave returned to Atlanta, I became inflicted with poison oak and soon found myself in the Shingle Springs urgent care receiving treatment for the allergic reaction to the urushiol oil. Poison oak covered hillsides at every location, and that time of year the plants do not have leaves, making them very difficult to identify. I spent much of my time over the next few days at the hotel frequenting a scalding hot shower to relieve the painful poison oak blisters and treating them with calamine lotion. The symptoms started to subside, and I readied myself to return to the field.

One of the bartenders at the Sierra Nevada House insisted that she would like to join us for a hunt. Mike Hankey and I had planned on meeting that morning on Cronan Ranch, so I invited her to come along. After leaving the parking area, we began the mile or more hike to the east bank of the American River. Mike and I had discussed meeting in the general area the night before, but I was very surprised when we walked up on his group huddled together in a grassy clearing.

Equally surprised, Mike hurriedly waived us over and pointed to the ground, where I spotted a beautiful meteorite laying on a large leaf. Mike was absolutely ecstatic. He explained to us that a local had asked to tag along at the beginning of their hunt, and it was this man who had found the piece, walking just a few feet from Mike.

Later that day, he made arrangements to purchase the stone from the finder. I know this meant much more to him in any other stone he could have purchased, as he had had a hand in its recovery.

Recovery Slows, and New Challenges Arise

More than a week went by with no more finds. I was hunting with a large group of professional meteorite hunters on a large, private ranch on the big end of the strewn field. Within a few hours, I found a small, oriented individual weighing less than one tenth of a gram lying in the rut of a jeep trail stretching across a steep hillside.

Over the next few days, lifelong friend and meteorite hunter Joe Franske and I scouted out every corner of the ranch. Neither we nor any other hunters made any further finds at that location. The small stone was and still is the smallest individual recovered from the Sutter’s Mill fall, and it is interesting that such a small individual stone was found so far down the big end of the strewn field.

Many more days of hard hunting would demonstrate the rarity of stones from this fall. Day after day of hard work, sunup to sundown, had produced just the two finds. I had once again come into contact with poison oak and had returned to urgent care – this time receiving injections to counteract the effects of this treacherous plant.

The lack of finds and conditions in the remote areas were wearing me down. Ticks had become more prominent, and several times a day I was picking them off of my clothes. In two cases, I found a tick attached to my shoulder, and one instance had exhibited a red, inflamed area around the bite. I was well aware of the danger from Lyme disease and kept a close eye on both areas where I had been bitten, looking for the telltale red bulls-eye. But I had no such symptoms.

New blisters from the poison oak were a daily occurrence, now that so much of the poisonous oil was in my blood. I was wearing down, both physically and mentally. A handful of the most serious hunters remained in the area. Camaraderie with them and news of new finds by locals, such as a rumored 35-gram stone, kept me pushing myself forward.

One evening I was talking with friends during dinner and felt that a breaking point was near and that I needed a change, perhaps a break. Right at that moment, my phone rang. It was Dave Gheesling.

A New Property to Hunt

He informed me that he had purchased the 35-gram stone from a local man, and that as part of the deal Dave and I would be allowed to hunt his property. Dave asked me to take possession of the stone the following morning and told me that the finder would line out on his property boundaries so I could hunt the area – and that he would arrive to meet me later the same day. The 35-gram stone was at the time the largest piece that had been recovered, making it the main mass. But the last thing Dave said to me was, “I expect you to find a bigger one before I get there.”

The next morning I met with the finder, and he took me on a tour of his property. I GPS-ed the corners as we went. About halfway through his tour, we were walking down an ATV trail along the northern boundary when, several feet to my left and barely out of the trail, I spotted what I had been looking for. A large individual meteorite lay perfectly tucked-in amongst a small patch of clover. I immediately began to shout, falling to my knees in awe at what I was seeing. I knew right away this would be the largest piece discovered to date!

We excitedly called Dave and left a message about the good news, knowing that he was in the air and would not receive the message until he landed. I felt a bit badly, as it is every meteorite collector’s ambition to possess the main mass from a fall. Dave had owned the largest piece for less than a day and had not even taken possession of it before my discovery had assumed the title of the new main mass. Without Dave’s acquisition, my find would have not been possible, and one of the most incredible pieces of the ancient solar system would most likely have never been recovered. Dave’s amazing people skills and charming personality once again were responsible for an amazing contribution to the meteorite world.

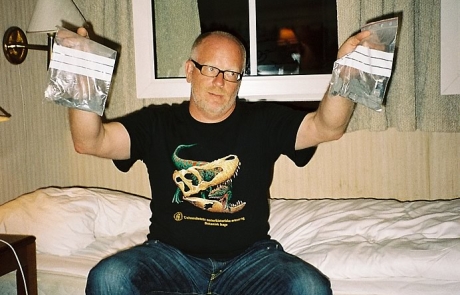

It is a shared story of acquisition and a turn of events leading to a most enlightening moment of discovery – one I will never forget and always share with a dear friend. Later that day, Dave arrived from Sacramento and was of course ecstatic to learn of my find. We had dinner with the landowner and his wife and celebrated later at the Sierra Nevada House. We felt like kings of the world, exhibiting the two largest pieces of the Sutter’s Mill fall to a roomful of scientists, enthusiasts, and professional meteorite hunters. Truly, it was a night to remember!

OSIRIS-REx, the Press, and a Problem

Having personally discovered the perfect trifecta of finds – the first find, the smallest find, and the largest find – I was finally able to breathe easily. I was run down and ready for a break.

I had been contacted by Dante Lauretta, from The University of Arizona, with respect to acquiring my first find. They required a pristine, pre-rain sample to calibrate the payload package for the OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample return mission, and I agreed to deliver the specimen to them in person the following day. A press interview was arranged, and after spending the night at my mother’s house in Bullhead City, I drove to Tucson early the following morning.

All of the material that I had collected was weighed and photographed with various members of the press in attendance. Dante Lauretta examined the specimens individually, and Dolores Hill cataloged and stored the research specimen.

I was conducting a National Public Radio interview when my throat suddenly became very irritated. Within a minute, I was unable to talk. Someone brought me water, and a short while later I apologized to the woman interviewing me and told her I could not continue. I said a very short goodbye to Dante and Dolores before driving home to Prescott.

The following morning I awoke around 11:00 am. I did not know where I was and was hallucinating. The room was shifting in fractal patterns. After some ten minutes, I realized that I was in my bedroom and that something was seriously wrong. I had been asleep for 14 hours.

I went to the hospital, where they started me on a regimen of antibiotics and tested me for Lyme disease. I had noticed a small black raised area in the center of the tick bite, and during my online investigations of Lyme disease encountered pictures of the symptoms from Rocky Mountain spotted fever. A telltale sign of this disease is a black, stool-shaped feature in the center of the bite called an eschar. Because I was bitten in California and this disease is almost unheard of in western states, the doctor found it highly unlikely but administered the blood test just to be certain. A week went by, and I received a call from my doctor informing me that the test for Lyme disease came back negative.

I was starting to feel better and wanted to get back to California to continue my work. Believing that I had endured an extremely aggressive flu virus, I drove back out to California and began hunting a few days later.

Rare Meteorites and a Rare Illness

I was hunting a large property owned by some new friends that I had made in the area when I began to feel very ill, unable to go more than a few hundred meters before becoming dizzy, disoriented, and fatigued. I had been trying to push myself for several hours when the phone rang; it was my doctor.

She asked, “How do you feel?” I replied that I felt terrible and explained my symptoms. She then informed me that the Rocky Mountain spotted fever test had back positive and instructed me to go to the nearest emergency room immediately to have my organ functions tested. My friends drove me to the Fulton hospital, where they administered an array of tests. After many hours, it was determined that my body was overwhelmed from flushing out the dead microorganisms but that my organs were functioning properly.

I did not regain my strength and soon returned to Arizona. It was several months before I was able to function outdoors with any normality. About a year later, I was contacted by a representative of the health department, inquiring about my incident with Rocky Mountain spotted fever. He informed me that I was the first confirmed case in 88 years in California, and that there had been many cases in the Yosemite area since. It seems I had been on a roll finding the first of rare things in California that year, although I certainly could have done without the latter having brought me to the edge of death.

The Sutter’s Mill meteorite fall was in most probability a once-in-a-lifetime experience – an opportunity to bring something extraordinary to science, as it is likely the oldest material known to man.

When it was first analyzed in labs around the world, it was believed to be depleted of organics, despite a mineralogy that suggested the opposite. It would be sometime before it was discovered that it is full of organics, the complexity of which made it impossible for earlier analyses to be made. This meteorite is so exotic that new methods of testing had to be developed in order to understand this most scientifically significant material.

IT WAS CLASSIFIED AS A CM2 CARBONACEOUS CHONDRITE.

Meteorite Details

| Name: | Sutter’s Mill |

| Location: | Sutter’s Mill, California |

| Classification: | CM2 |

| Witnessed: | Yes |

| Fell: | April 22, 2006 |

| TKW: | 952.7 gm |