Expedition Journal

New Bolivia Fall

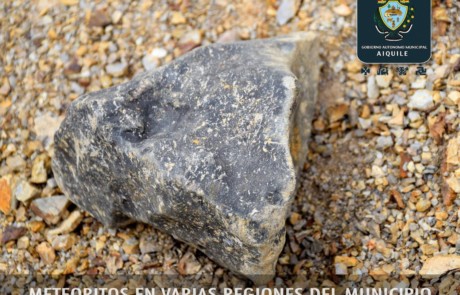

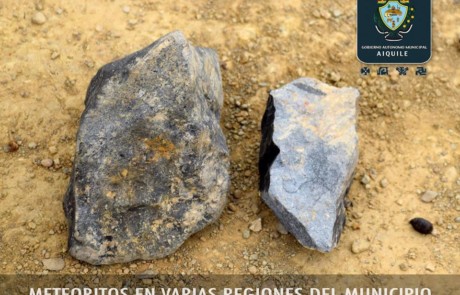

On November 20, 2016, a daylight fireball entered the atmosphere over the Andes Mountains near Aiquile, Bolivia. Spiraling towards Earth, it begins to break up as it entered the lower atmosphere, producing four distinct sonic booms that roared down the canyons below – terrifying the local Quechua Indians as they witnessed a dark cloud travel across the sky in a fraction of a second, leaving a brief persistent train in its wake. The Quechua soon began to find strange black rocks scattered throughout the red dirt hills, in and amongst their villages that dot the canyons.

The event made headlines in the Bolivian news but remained surprisingly quiet in international news. Soon after learning of the event, I had tickets booked for a four day expedition to the area. After arriving in Cochabamba, I got a taxi and began a harrowing trek through the Andes Mountains during a massive storm that produced rock slides and several inches of snow. The taxi driver had never seen snow before and stopped to video the unusual phenomenon several times.

I arrived at the Hotel in Aiquile on the evening of December 2nd, and began to map out a plan for determining the flight path of the meteor and the strewn field distribution.

The Hunt Begins!

The following morning, my driver drove me up the canyon to where pieces have been found, and I GPS’d the find location for two stones in the five-kilogram range. I had the driver drop me off on the road above the village and hiked into the foothills in search of stones. I had been on the hunt for just over an hour when I heard whistling from the ridge line across from me. The person was on horseback and signaling to the other villagers below; I knew that I had been spotted.

I called my driver and instructed him to pick me up on the road, then made my way down the mountain through heavy brush and crossed a cow pasture between two huts in order to access the road unseen. After my driver found me on the road, I returned to town. That evening I ate chicken and noodles at The Pollo Cluck, a restaurant near the hotel that was run by a Chinese family. As our food arrived, so did a variety of dogs. Every breed and size stopped by my table with a pitiful stare. I was informed that area had been under an intense drought for some time and that many farming families had left – leaving their animals behind, including their prized, purebred dogs.

The next day, I had the driver take me to an area where it was rumored that the 35-kilogram main mass stone had been found – before it was confiscated by the local police. I picked up a man walking down the road who happened to live in the area where I was heading. He kindly took me to the spot where the big stone had been found. After GPS’ing the 35 kg stone’s impact location, I had a very good sense of the actual flight path. I was given permission to hunt the area, and for many hours I made my way up the flight path towards the area where 5kg stones had been found. But no finds were made.

My third day of field work began with an arduous trek across a deep canyon, up the side of a steep mountain range that lies between the fall sites of 5 kg stones and the 35 kg stone. Across the canyon, I discovered a very old Quechua ruin perched on a steep mountainside that was overgrown with cactus. Several hours later, I ambled onto a flat summit overlooking the entire strewn field. The ground was superb for hunting large stones. I estimated that 8-to-20 kg stones could have landed in this area, making it a prime focus for my search.

I had worked my way by mid-day down to nearby the village when I spotted a goat herder heading up a mountain trail towards me. I worked my way up a ravine and laid low as I watched him pass by with his flock with a baby goat in his arms. I hunted back up the mountain, as I was running low on water and still had a long trek to get to my pick up location. Noticing some cows below the summit, gathered around deep ravines, I hiked over on a hunch and located several pools of water where I was able to filter and refilled my supply to a safe level for the long journey down the mountain. This day alone, I walked 13.7 miles and climbed the equivalent of 175 floors.

Difficult Hunting

The following day, I decided to hike in towards the village from the opposite side of the flight path in hopes of finding the small end of the strewn field. The driver dropped me down a ridge line that appeared to intersect with the mountain range. Unfortunately, I discovered that the ridge ended at a valley dotted with huts between me and the mountain. I crossed the valley carefully. But as I began the climb up the mountain, a man riding horseback began shouting at me. I paid no mind and continued my climb.

After an hour or so, I had made it halfway up the mountain and began to skirt the side overlooking the village bellow. I soon ran into a major obstacle: the mountain range had been split by tectonic movement, and a 200-meter gap separated the mountain range into two halves. I hiked down into the gorge and started back up again, knowing the same amount of work I had just endured to get to the top of the mountain now laid before me yet again. After several hours, I made my way into the flight path of the fireball and began to hunt.

I was in a small valley, unseen from bellow and nestled between two ridge lines of rock, forming the edges of the mountain range. The area was dotted with a few dirt and rock huts, now abandoned because of the severe drought that has plagued the region for several years. I hunted several fields and pastures as I made my way down the flight path, dropping off onto a shelf perched a third of the way down the mountain that featured gullies carved from red clay by the torrential rains, snaking down the steep ravines into the valley below.

The Recovery!

I dropped off the shelf onto a small flat area where I made my way down a ravine that took me two-thirds of the way down the mountain. I chose a small rock bench about a hundred meters or so across that had been pushed up by an earthquake untold eons ago. Climbing onto it, I began to pick my way through the sparse brush.

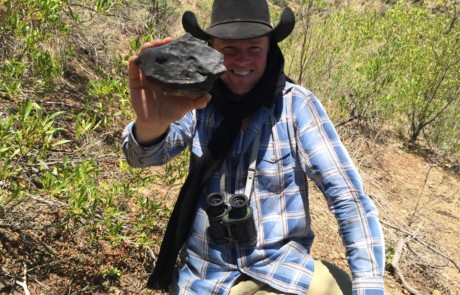

It was no more than a few minutes when it happened – the moment when everything changed and those hard hours started to fade away. Twenty meters away, below a small willow tree, I spotted a familiar angular shape. Deep-black against the red clay, an intact stone of 1.285 kilograms sat majestically in the bright sunlight!

I took GPS coordinates of the location, photographing the stone in-situ before carefully wrapping it in my alpaca scarf and tucking it in my pack.

I continued to hunt the bench, worked my way over to the edge and surveyed the area below with my field glasses. Several hundred meters below, I saw a young girl heading up the canyon towards my location. Moments later I heard footsteps just meters away. A very angry Quechua man bursts out of the bushes yelling with his chest puffed out, waving his arms in the air. I began to talk to the man, who after some time calmed down. We sat under a bush and I explained the dynamics of the meteorite fall to the man, and offered to buy stones he had found.

Eventually I hiked back down the mountain to the road. At the bottom of the canyon, I started walking the main road back towards Aiquile. With no phone reception to contact my driver, I walked the full eight kilometers back into town. I was smiling the entire way.

Escaping the Chaos

I ran into several South American meteorite dealers when I returned to the hotel, and I began to get an uneasy feeling – knowing full well from experience the chaos that is surely soon to follow. And that evening I make the decision to head home with my incredible find.

I chartered a bus to take me to Santa Cruz, and I soon departed on the 12-hour journey. Unfortunately, due to a lack of seats, I ended up sitting on the steps at the front of the bus and endured an absolutely miserable journey through washboard mountain passes. At one point, the bus was delayed by a large truck hauling construction materials up the mountain that had become stuck in the middle of the road. It was freed after an hour or so of digging, and I began my journey once again.

After the longest bus ride of my life, I arrived at the Santa Cruz airport. The stone was flagged at all three security check points, but with a little persistence they allowed me to keep it in my carry-on luggage. Soon the rock and I were in the air, and the city of Santa Cruz faded out of sight in wispy clouds – the peaks of the Andes Mountains jutting through them like islands floating in the Incan sky.

IT WAS CURRENT AN UNCLASSIFIED ORDINARY CHONDRITE.

Meteorite Details

| Name: | Aiquile |

| Location: | Aiquile, Bolivia |

| Classification: | Chondrite, pending |

| Witnessed: | Yes |

| Fell: | November 20, 2016, 17:00 Local |

| TKW: | Pending… |